Berger code

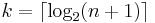

In telecommunication, a Berger code is a unidirectional error detecting code, named after its inventor, J. M. Berger. Berger codes can detect all unidirectional errors. Unidirectional errors are errors that only flip ones into zeroes or only zeroes into ones, such as in asymmetric channels. The check bits of Berger codes are computed by summing all the zeroes in the information word, and expressing that sum in natural binary. If the information word consists of  bits, then the Berger code needs

bits, then the Berger code needs  "check bits", giving a Berger code of length k+n. (In other words, the

"check bits", giving a Berger code of length k+n. (In other words, the  check bits are enough to check up to

check bits are enough to check up to  information bits). Berger codes can detect any number of one-to-zero bit-flip errors, as long as no zero-to-one errors occurred in the same code word. Berger codes can detect any number of zero-to-one bit-flip errors, as long as no one-to-zero bit-flip errors occur in the same code word. Berger codes cannot correct any error.

information bits). Berger codes can detect any number of one-to-zero bit-flip errors, as long as no zero-to-one errors occurred in the same code word. Berger codes can detect any number of zero-to-one bit-flip errors, as long as no one-to-zero bit-flip errors occur in the same code word. Berger codes cannot correct any error.

Like all unidirectional error detecting codes, Berger codes can also be used in delay-insensitive circuits.

Unidirectional error detection

As stated above, Berger codes detect any number of unidirectional errors. For a given code word, if the only errors that have occurred are that some (or all) bits with value 1 have changed to value 0, then this transformation will be detected by the Berger code implementation. To understand why, consider that there are three such cases:

- Some 1s bits in the information part of the code word have changed to 0s.

- Some 1s bits in the check (or redundant) portion of the code word have changed to 0s.

- Some 1s bits in both the information and check portions have changed to 0s.

For case 1, the number of 0-valued bits in the information section will, by definition of the error, increase. Therefore, our berger check code will be lower than the actual 0-bit-count for the data, and so the check will fail.

For case 2, the number of 0-valued bits in the information section have stayed the same, but the value of the check data has changed. Since we know some 1s turned into 0s, but no 0s have turned into 1s (that's how we defined the error model in this case), the encoded binary value of the check data will go down (e.g., from binary 1011 to 1010, or to 1001, or 0011). Since the information data has stayed the same, it has the same number of zeros it did before, and that will no longer match the mutated check value.

For case 3, where bits have changed in both the information and the check sections, notice that the number of zeros in the information section has gone up, as described for case 1, and the binary value stored in the check portion has gone down, as described for case 2. Therefore, there is no chance that the two will end up mutating in such a way as to become a different valid code word.

A similar analysis can be performed, and is perfectly valid, in the case where the only errors that occur are that some 0-valued bits change to 1. Therefore, if all the errors that occur on a specific codeword all occur in the same direction, these errors will be detected. For the next code word being transmitted (for instance), the errors can go in the opposite direction, and they will still be detected, as long as they all go in the same direction as each other.

Unidirectional errors are common in certain situations. For instance, in flash memory, bits can more easily be programmed to a 0 than can be reset to a 1.

References

- J. M. Berger, "A note on an error detection code for asymmetric channels", Information and Control, vol 4, pp. 68–73, March 1961.

- Subhasish Mitra and Edward J. McCluskey, "Which concurrent error detection scheme to choose?", Center for Reliable Computing, Stanford University, 2000.

- "Delay-Insensitive Codes -- An Overview" by Tom Verhoeff